Teaching a Nation

Teaching a Nation

Almost 4,000 kilometres from Halifax, a group of Mount educators is helping a nation transform its approach to primary school education.

More than 1,500 teachers (or about half of all grade-school teachers in Belize) have graduated from a professional development program, provided by the Mount in partnership with the Belizean Ministry of Education, Youth, Sports and Culture. It’s a program that has sought to support the primary school teachers of that Central American country in their efforts to implement a new student-centered teaching style.

Dr. Andrew (Andy) Manning and Alan Dawe of the Mount’s Faculty of Education have been running the program for Belizean teachers since August 2015. This five million US$ project funded by the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) began with the Belizean Ministry of Education Youth, Sports and Culture’s push to improve education in their primary schools.

“The chance to impact an entire nation is a rare opportunity, and one that we are most grateful for.” – Alan Dawe, Faculty of Education

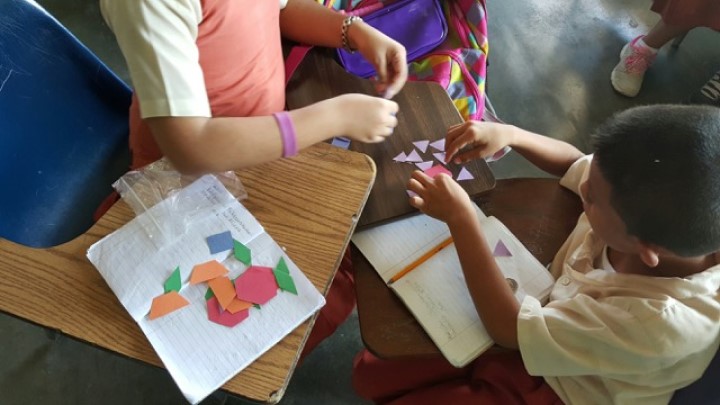

“There was a concern that the teaching style was outdated,” Alan, coordinator of the program, explains. “The Ministry wanted to move to a student-centered, hands-on pedagogy.”

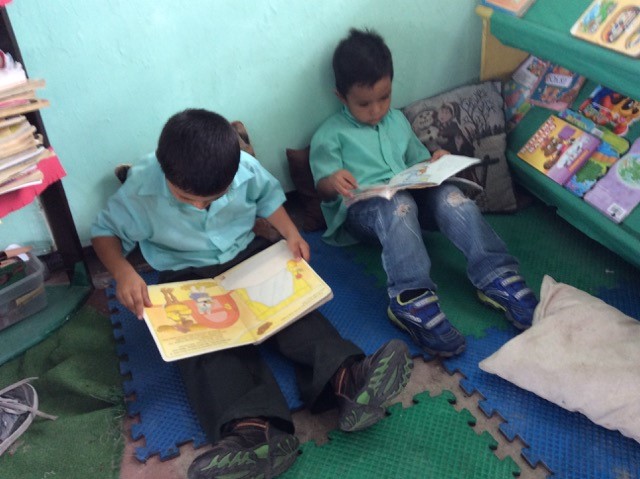

Approximately 115 primary schools in Belize (about half of the country’s schools) have participated in the program through which the teachers and administrators at those schools have incorporated new teaching methods for math, science, and language arts into their classrooms. The initial focus of the project was on teacher professional development. A second component was added mid-way through the project to design and deliver a program on instructional leadership for school administrators.

While everything is based on the Belizean curriculum, Andy and Alan note that the program’s content had to be developed from scratch in order to effectively introduce student-centered teaching techniques in the region.

“The process to become a teacher in Belize is different than ours,” Andy explains. “Most teachers do not have an education degree, and some are straight out of high school – they get their teaching license and then have five years to get the appropriate training. Consequently, there is a concern that some Belizean teachers don’t know the content, but when we demonstrate how they should teach their students, it in turn teaches them the content. Everything we do is a model for teachers to emulate.”

Andy and Alan are well versed in international education programming.

“We have run education projects in Jamaica, Trinidad, Guyana, Barbados and even Abu Dhabi. Most of what we have done has been in developing countries, but this [Belize initiative] is the longest project we have been part of,” says Andy.

Coaching – a key part of the program

In addition to professional development workshops, teachers participating in the program have been coached by volunteer Canadian teachers and Belizean teachers seconded from their schools.

More than one hundred workshop instructors and coaches have participated so far – most of them Nova Scotian teachers. They’ve travelled to Belize where they’ve been connected with local educators in a way that fosters collaborative, mutual learning.

“The coaching began with Canadians; however, we have now identified a cadre of local educators who have been seconded to the project and are serving as local coaches,” Alan says.

According to Alan the coaches are an invaluable part of the program. Many have done multiple missions, and support ongoing communication between students and educators in Belize and Canada. They’ve also been critical supports as the teachers in Belize sought to implement their newly acquired instructional strategies – providing direct support in the classrooms.

Programming rooted in Belizean culture

While rewarding, the work hasn’t been without it’s challenges for Andy and Alan. The schools in Belize are remarkably diverse: most schools are denominational, and some are inner-city or suburban, while others are in small villages – some with no water or electricity. And while certain aspects of effective teaching and learning are universal, the importance of providing culturally-appropriate training (in format and content) is central to the program’s success.

“You have to walk through the jungle to get to the most remote schools, so it isn’t uncommon to be delayed because there has been a jaguar sighting,” Alan laughs. “Not to mention the mosquitoes are horrendous; I couldn’t guess how many gallons of insect repellent we have used!”

In addition to the wildlife, Andy and Alan note that the weather has been a significant setback for them at times, including a hurricane in 2016.

“We had purchased 12 tons of supplies for the schools from China. Some had been moved to a warehouse that, during the hurricane, ended up under six feet of salt water. We didn’t have insurance on the temporary location and it took months to try to restore everything. We managed to rescue it all, but in many ways, we’re still recovering from that setback,” Alan says.

What’s Next As in all IADB funded projects, there was a program evaluation component. “The 50% of Belizean schools we worked with were randomly selected, with the other 50% acting as a control group. Initial data points to successful implementation and plans are underway to duplicate the program with the control group schools,” says Andy. “We are currently heavily into logistic planning to roll out this second phase.”

As in all IADB funded projects, there was a program evaluation component. “The 50% of Belizean schools we worked with were randomly selected, with the other 50% acting as a control group. Initial data points to successful implementation and plans are underway to duplicate the program with the control group schools,” says Andy. “We are currently heavily into logistic planning to roll out this second phase.”

One of the goals of the first phase was to build capacity in Belize to sustain the change in pedagogy. The new phase will be more locally driven as it draws on the local capacity built in the first part of the program. “We thought this program would be our swan song for international work but it looks like that is now a few more years away,” says Andy.

“We consider ourselves lucky, “Alan concludes. “Belize is a beautiful, amazing place, and this experience has been unparalleled. We have had the chance to work with all ethnic groups, including Creole, Garifuna, Mayan and Mestizo, and we have received incredible gratitude from the community, parents, and the Ministry. We have been part of something greater than ourselves. In order to do what we do, you need a dedicated, effective team, and we are tremendously grateful to the Belizeans and Canadians that have been part of this journey with us.”