Jacquie Gahagan, Mount Saint Vincent University and Denyse Rodrigues, Mount Saint Vincent University

Many older lesbians sought out invisibility, they called each other “friends” or “career girls” or “not the marrying kind.” These terms worked as camouflage and helped many women feel safe during a time where their sexuality wasn’t accepted.

And while invisibility was at times a “necessary fiction,” there were many other factors that contributed, including lesbophobia. Lesbophobia is a type of discrimination affecting women who are attracted to women because of their sexual orientation.

Over the past several decades, identity terms — like lesbian — have gone through cycles. Words coined by 2SLGBTQQIA+ communities are often misused until they become insults, but these insults can be reclaimed.

“Lesbian” was reclaimed by activists in the 1960s, just before the community adopted “LGBT,” which grew to become the more inclusive “2SLGBTQQIA+.” And while still a contested term, the next generation began to reclaim the term “queer.”

We’re involved in community projects called the Nova Scotia LGBT Seniors Archive and Lesbian Oral History Project that focus on gathering stories from the generation that began using lesbian, and those who still can’t.

2SLGBTQQIA+ history cannot be complete without these women’s stories, but breaching their fiercely protected invisibility raises ethical questions: Can we describe them in their own language?

Why does this matter?

The generations of lesbians who were instrumental in the early fight for equal rights and protections for 2SLGBTQQIA+ Canadians are now in their senior years. Despite their efforts to advocate for change, the stories of older lesbians often go unnoticed or underappreciated.

Older lesbians are not an invisible artifact of the times, but rather the keepers of a rich history of the lives of women who love other women. We have found that there is a struggle for our stories to be heard. As many of us age, we risk losing this rich history. But lesbian oral history archival projects — like ours — are helping counteract this.

Oral histories can create intergenerational teaching and learning opportunities for people to understand the struggles and hard-fought wins.

By lesbians for lesbians

The long history of 2SLGBTQQIA+ discrimination and hatred has led to an under-appreciation of the various contributions made by lesbians in advancing human rights legislation.

As part of the recently founded Nova Scotia LGBT Seniors Archive, the Lesbian Oral History Project is collecting the stories of older lesbians from across Nova Scotia to preserve and share our history.

Through community consultations, the Nova Scotia LGBT Seniors Archive became aware of the lack of archival records in the province pertaining specifically to older lesbian histories, including their contributions to Nova Scotia history in general and 2SLGBTQQIA+ history more specifically.

To mitigate this lack of representation, the archive sought funding from the provincial government to develop the Lesbian Oral History Project, which will allow older lesbians (specifically those born between 1946-64) across Nova Scotia to share their stories.

The oral histories were collected over a two-year period, recently transcribed and will be included in the larger Nova Scotia LGBT Seniors Archive collection at Dalhousie University.

It was necessary for the Lesbian Oral History initiative to be run by lesbians because of the importance in being mindful of who controls the process of visibility and with what motives.

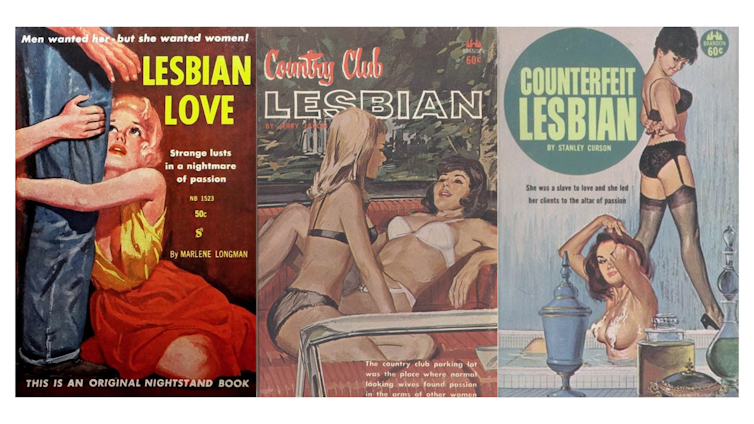

For example, in the 1950s and early 1960s, when many of today’s lesbian seniors were in their youth, lesbian pulp fiction with sensationalized covers sold millions of copies providing one of the few sources of lesbian representation in an era known for its repression of sexual minorities.

(Wikimedia Commons)

The majority of these books were written by and aimed at cisgender straight men. The books often contained tragic endings and moralistic messages against gay men’s and lesbians’ so-called lifestyles — their legacy remains today with “Bury your Gays” and “Dead Lesbian Syndrome” tropes.

Despite the publishers’ constraints and who they were written by, many of these books formed what became known as “lesbian survival literature.” The stories depicted queer women living and loving in difficult times, where desire and self-determination were more important than happy endings. It helped many lesbians of that era feel seen despite not being the target audience.

Our projects — the Nova Scotia LGBT Seniors Archive and the Lesbian Oral History Project — hope to do what lesbian pulp fiction did for many lesbians in the ‘50s and ’60s — help them feel seen. But we’re doing it differently as the Lesbian Oral History project is created by and for lesbians.

We need to see additional systemic changes in, for example education, to ensure these important contributions of older lesbians are not lost.

This piece was co-authored by Anne Bishop an activist, author, educator, food security advocate, labour organizer and community development worker. Since the 1980s she has advocated for LGBTQ rights, union organization, equity and anti-racist policies in the province of Nova Scotia.![]()

Jacquie Gahagan, Full Professor and Associate Vice-President, Research, Mount Saint Vincent University and Denyse Rodrigues, Library Research & E-Learning Services Librarian, Mount Saint Vincent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()